Instead of spending a lot of our time working on the house, recently we’ve just enjoyed being there, looking after the garden and pond, which together can take up a lot of time. This post is a pause for thought about what’s next.

We’ve carried out no substantial work other than maintenance for 6 years, but there are several bigger jobs piling up that need doing, and it’s time to start thinking about them.

To begin, a reminder of what we’ve already done: major work in 2008-9 made the building habitable, and this included the replacement of rotten oak soleplates on which the wall timbers rest, and the installation of electricity, water and sewage from scratch – the little building had been a house, but was unlived in for hundreds of years. These big projects were mostly done by professionals, as was the construction of the extension in 2014.

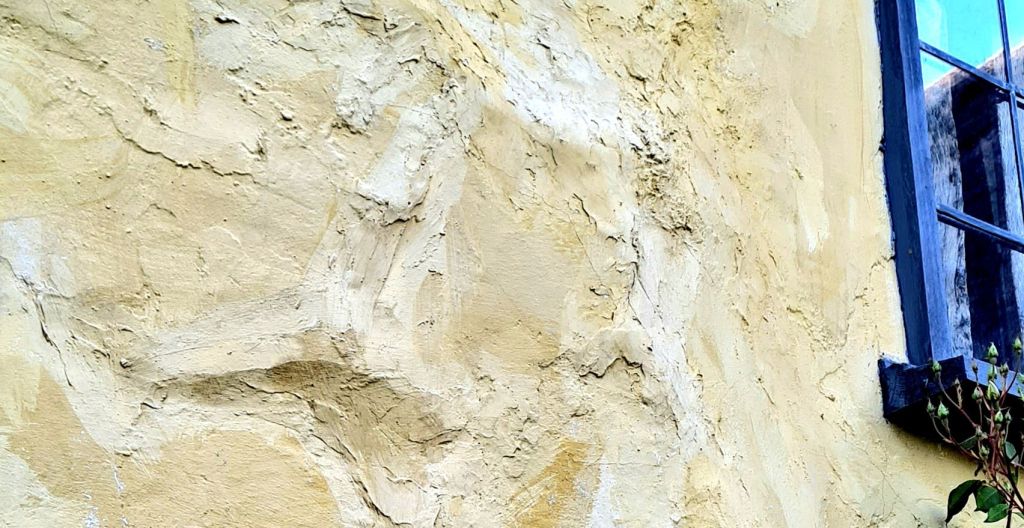

There were also a large number of ancillary jobs that we either tackled ourselves or did with professional help and advice over the years. They included repair of damaged walls with new clay daub, removal of old cement render used by previous owners and its replacement with lime, stabilising sections of two clay side walls, lime plastering and repairing inside walls and ceilings, limewashing the whole house inside and out and a host of smaller jobs described in this blog.

The most pressing work now is the north gable, where there are cracks and breaks in rough cement render applied in the 20th century, revealing ancient clay daub underneath. That is overdue for stripping back to the clay, which will need repairing and then re-rendering.

When we repaired the south gable we covered it in porous Savalit boards before plastering, to give extra insulation and protection, and we need to do the same again. The work will need scaffolding and professional help.

Secondly, we patched large holes in the side walls with clay in 2009. But other weak areas of the old wall material were preserved in place by using chalk lime plaster mixed with fibres to stitch over the cracks to slow further deterioration.

That was a relatively short term solution, though it has lasted a dozen years. We need to think now of more thorough repairs, which we can tackle ourselves.

Thirdly, the roof needs attention. A worrying number of the clay peg tiles have frost damage. Luckily, we have several hundred recycled tiles left over from construction of the garage. A roofer tells us that it is feasible to replace damaged tiles, though tricky because of the way the peg tiles are laid with nails. But we want to avoid full stripping and repair, which would involve negotiation with the heritage department, and a lot more expense.

There’s a list of other smaller repairs which has lengthened as we have focused on the pond and garden, so it will be good to practice on those before we gear up towards larger projects.